A visitor to Versailles in the 1750s

A few years ago I contributed with a translation of parts of the Swedish physician Roland Martin’s French travel diary from the 1750s to the database ”Visiteurs de Versailles” hosted by the Centre de recherche du Château de Versailles. Martin was in Paris to study surgery, but as any visitor to the European metropolis he took the opportunity to visit some of the most notable sights in the area, among them Versailles.

Roland Martin visited Versailles at three separate occasions: in September 1754, and June and August 1755. He went to see all the major sites within the palace and the park, including Marly, and he was eager to catch glimpses of any member of the royal family. There was nothing unusual with Martin’s excursions – Versailles was open to visitors already in the seventeenth century, providing they were neatly dressed and behaved properly. But what is particularily valuable with his account is the level of detail he paid to practical issues: how he got from Paris to Versailles (by rented coach), how he prepared for the entry to the palace (by powdering his wig at the barber), how he and his company catered for their meals during the visit, what everything cost, and many other details about ordinary visitor routines.

I am pleased that Martin’s interesting exposition of his visits to Versailles is included in the Centre de recherche’s extensive database on travel accounts from the ancien régime. That way it can become known to researchers. Less pleasing is that the database is inacessible to ordinary visistors. Therefore I decided to publish my own translation here together with some contemporary images and my own photos from Versailles.

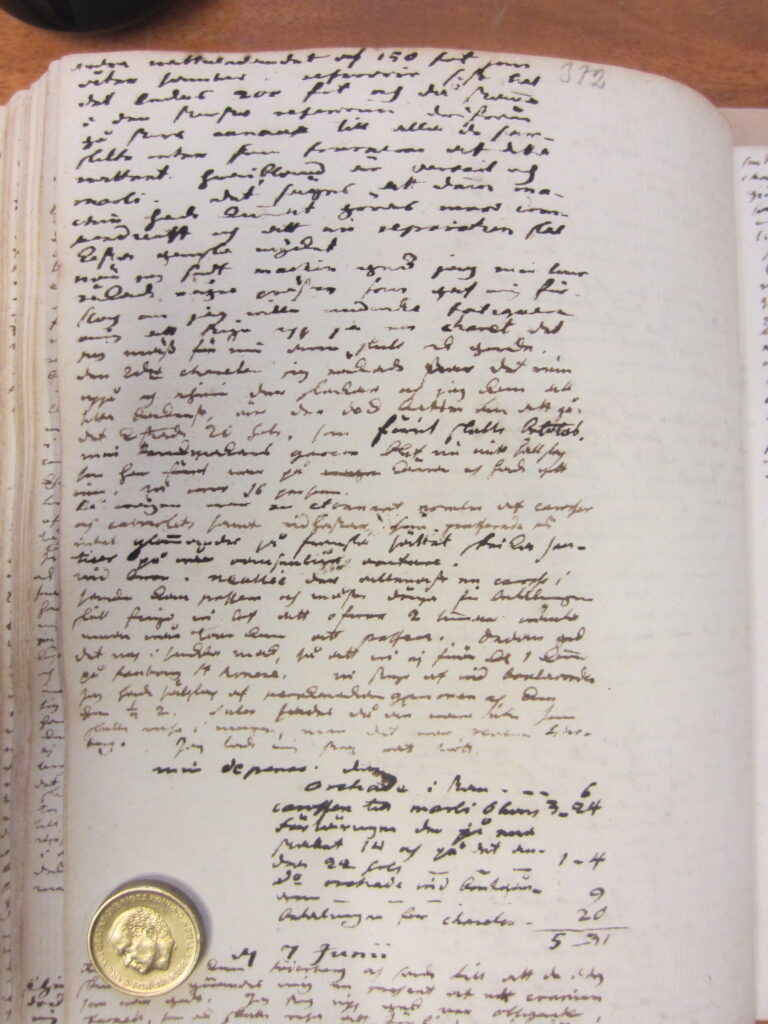

I used Martin’s diary when I wrote my book Versailles: Slottet, parken, livet (Versailles: Palace, Park, Life), which was published in 2013. The manuscript diary is kept at the Hagströmer Library, the medical historical collections of Karolinska institutet, as Ms. no. 126. Perhaps Roland Martin was set on keeping his travelogue within the limits of a single volume. However that may be it is written in miniscule script, which makes it hard to read at times (cf. example below). I have therefore benefitted from a transcript of the diary made by Helga Lindström in the mid-1900s, I believe, possibly with the intent of publication. (It is kept at Uppsala University Library among the papers of Professor Johan Nordström, vol. 23, 496 b:1.) Before I dicscovered this clean copy of the text I had already made a transcript of my own, and I have been able to compare my own reading with that of Lindström, which has straightened out most question marks.

The transcript presented here has been further revised compared to the English translation I previously provided to the Versailles research centre. It has been my ambition to maintain something of the eighteenth-century way of expression in the English translation.

A pdf with the whole text, without images, can be downloaded here.

Roland Martin, Diary 1754–1756.

Manuscript no. 126, The Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm

Transcript and translation by Jonas Nordin, Lund University. CC BY 4.0

21st September [1754]

[- – -] Later I followed Mr Suther to Dr Lindhult, where we sat down for a while and among other things agreed to go together next week to Versailles, where we among other things would have the chance to see King Stanislaus, who had travelled for a few days’ visit to his son-in-law, the King of France. [- – -]

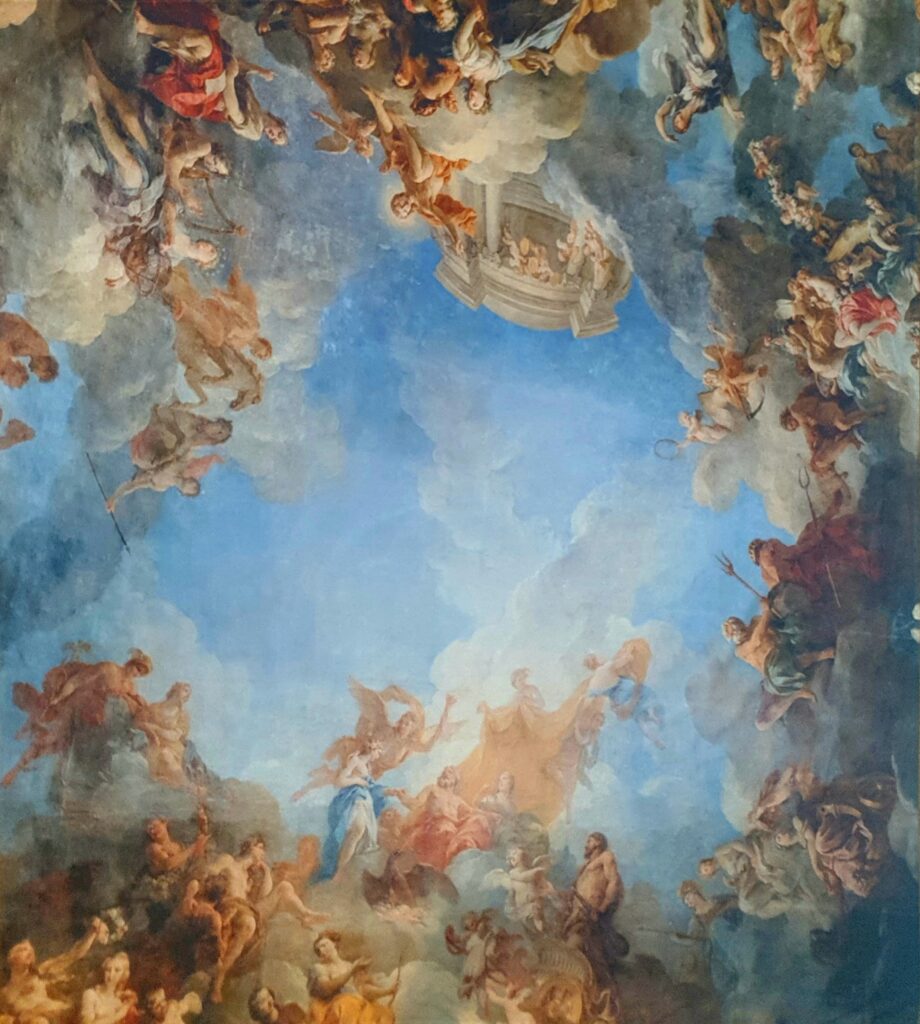

24th September I rose at six o’clock to go to Versailles as agreed. Dr Lindhult came to me at half past six and since I had promised to ask Mr Suther, I first went to him, while Dr Lindhult went to Lieutenant Freitack, where we all would meet. Mr Suther did not want to go, but he resolved with me to go anyway. We all gathered at Lieutenant Freitack’s from where we, after having had breakfast with wine and bread, set off for the journey. Mr Suther and I took to travel in a pot de chambre, which cost each of us 3 livres 10 sols. We left Paris at eight o’clock and arrived in Versailles at half past nine. We went to an inn to accommodate our wigs and thence to the palace, where anyone who desires is allowed to enter and stroll in the splendid gallery. The first room was adorned with the most magnificent piece of painting in the ceiling,⨯ which depicts Olympus with all the gods assembled around Jupiter and Juno along with the Parnassus with Apollo and all the Muses.⨯⨯

| ⨯ [RM’s marginal note:] The great painters Raphael, Rigaud, Guido [Reni], and le Brun are the authors of most of these pieces of art. | |

| ⨯⨯ [RM’s marginal note:] N.B. this painted ceiling is said to have been painted by the great Le Moyne and it is one of the largest paintings in the world. However, when its master had finished his work, because of some personal grudge that the prime minister harboured towards him [illegible], he was asked what he demanded in compensation and how much the paint had cost, whereupon he became so furious that he immediately stabbed himself to death. |

Another room, which was a corner room, was called Salon de Guerre in which Bellona was sitting over a chariot pulled by raging horses that knocked down and trampled everything in their way that bore a mark of holiness, erudition or the arts. Love was fleeing from them with her children. In the longest gallery all of Louis XIV’s achievements were represented each for itself between round pillars (columns) of costly marble. Here were also several busts of ancient Romans. In addition, there were mirrors at the floor on both sides. In another room is a Salon de Paix, situated outside the rooms of the Queen, but I was not allowed to see it.

At ten o’clock the royal family went to Mass and King Stanislaus was the first to leave his rooms surrounded by a large retinue of men. Mr Suther and I was standing in a gallery and were so lucky as to look him in the eyes when he passed by, whereupon we followed him to the church and got a good view of him. He was kneeling a long time before an altar and then returned, whereupon we took position once again to have a closer look at him. The Gentleman was squat and corpulent, somewhat crooked by age, leaning on two men who walked beside him of which one was his abbot. He was wearing a plain brown silk dress with a star on his chest, which was the Order of the Holy Spirit with the blue ribbon underneath the coat and over the waistcoat. He nodded slightly to those he noticed on the sides when he passed, always putting on his hat as soon as he left the church and until he reached the galleries.

At half past ten the Queen arrived to attend Mass;⨯⨯⨯ she had a benevolent appearance, not showing the slightest trace of haughtiness or pride. She resembled a lady I know in Stockholm, who is a widow and has been married first with Gabriel Diupenström, later with Burman or with Kempi’s wife in Halmstad [sic]. She [the Queen] never had any gold or silver on her clothes but wore a plain red silk dress and fingerless handwear of linen in her hands. We followed her to church, where she devoutly stood on her knees.

| ⨯⨯⨯ [RM’s marginal note:] The French say: ”La Reine est extrêmement bonne, elle a une aire aisée sans façon et sans hauteur, comme une bourgeoisie. C’est pourquoi elle est aimé de toute la France.” [The Queen is extremely kind; she has an easy, unpretentious manner without arrogance, like a bourgeois woman. That’s why she is loved by the whole of France.] |

The church is embellished with grand ornaments and large works of art, and it has a gallery running like a stand around the whole of the interior. Here stood the King’s and the Queen’s confessionals opposite the largest altarpiece, or at one end of the church with the said altar on the other. There are several altars on the sides, and after re-entering the church we coincidentally positioned ourselves next to where the Dauphin was standing with a company of gentlemen and his guard. At first, we did not know who it was, but Mr Suther soon realized. This gentleman looks fleshy and somewhat negligent, he has a confident look and a steady, not to say uncouth, walk. Before the Mass was over, we left to be in position to see them pass by once more in the gallery, which also happened. We now ran into our companions who had walked here and were displeased of having arrived too late to see King Stanislaus.

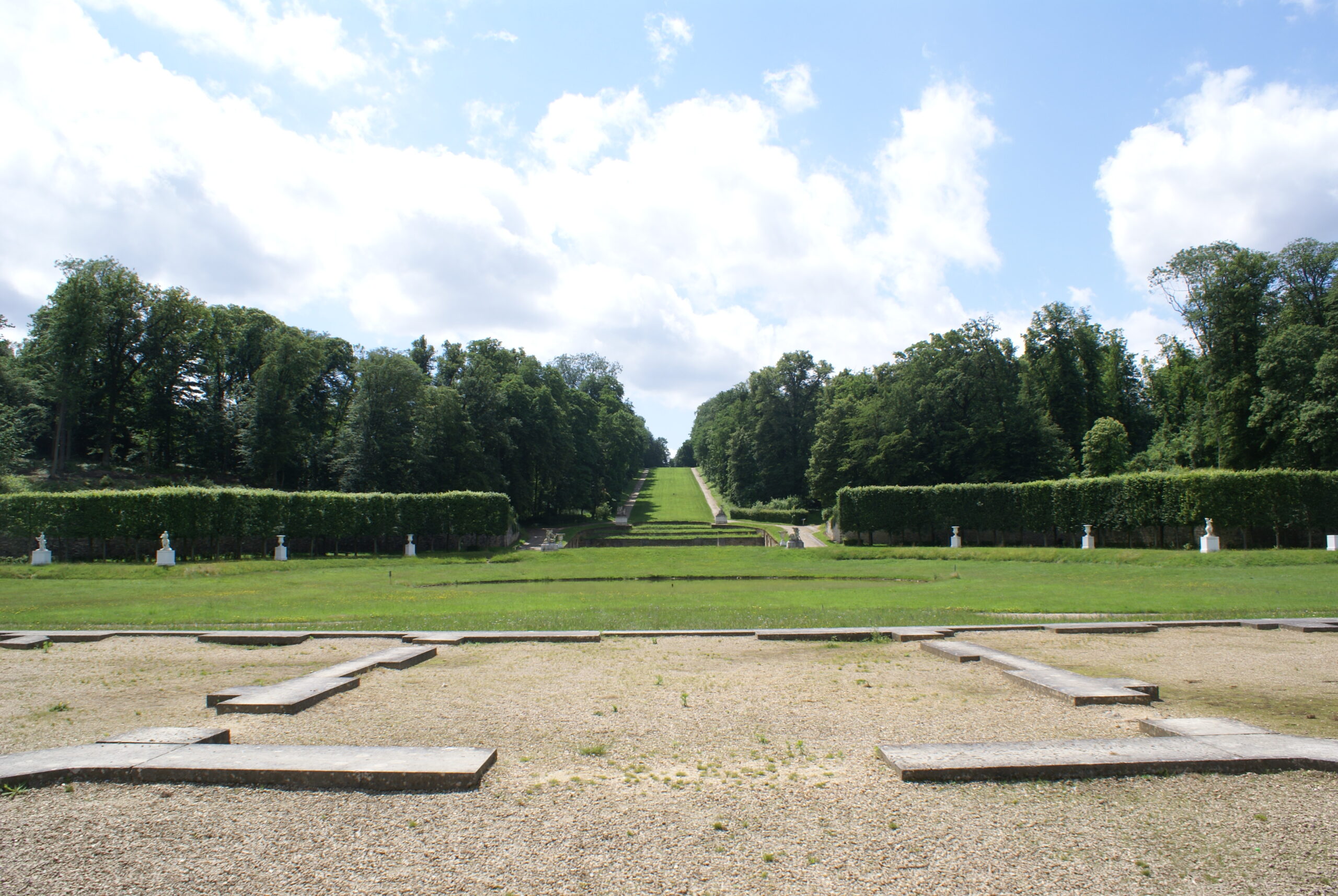

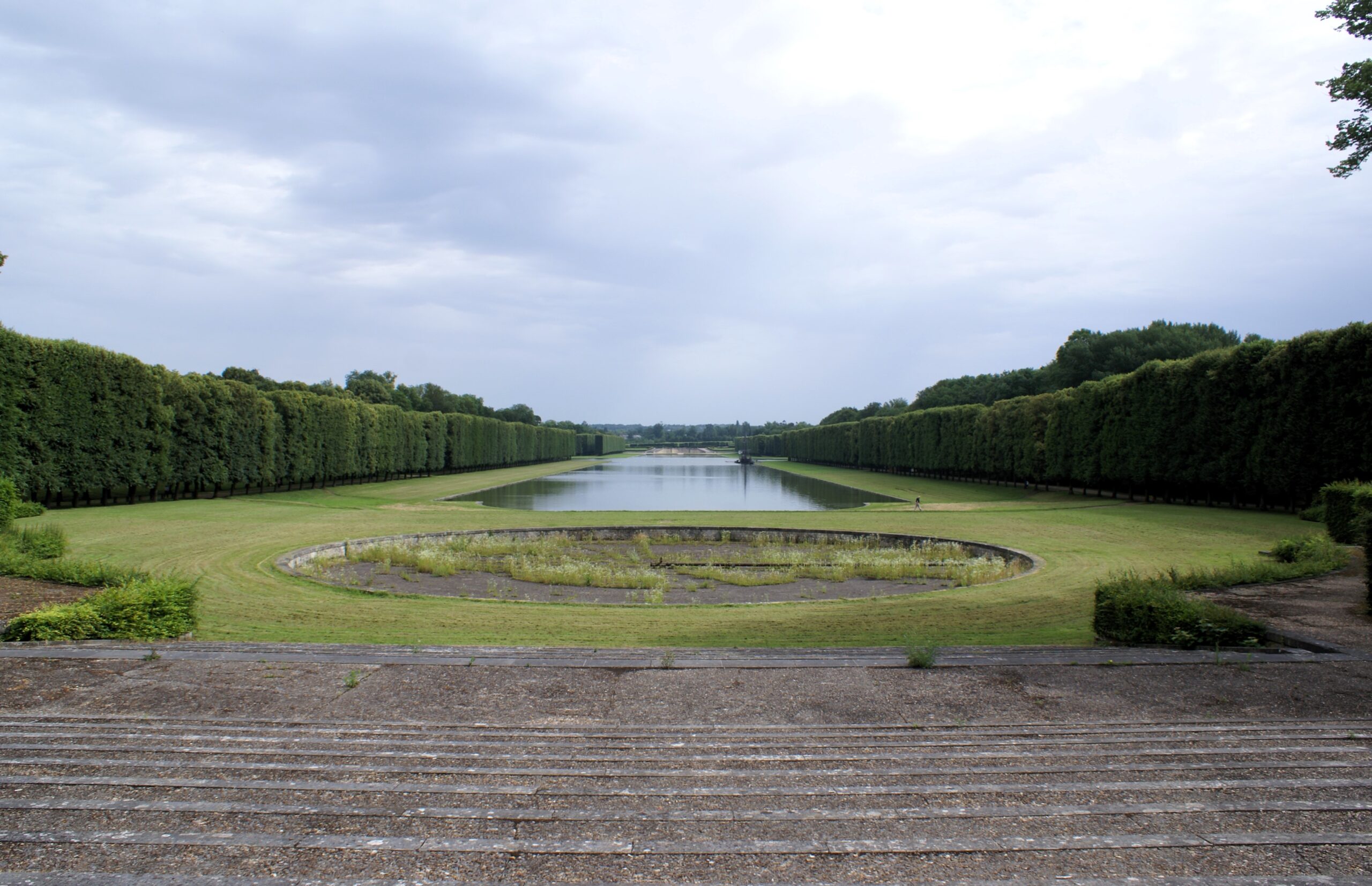

We then proceeded to the gardens, in which one of the wonders of the world are surely to be seen in the magnificent marble statues of gods, goddesses, heroes and all sorts of postures, as well as the ponds or bassins where the fountains (jets d’eaux) are made. Any [printed] description of Versailles can give a more accurate account of all this than I am able to. I am only happy to have had the luck of seeing it all. We went past the bosquet de Colonnade but did not want to enter until afternoon when it was coloured [by the sunset]. We paused for a while by the Tapis Vert, which is a big green plane at the bottom, near the pond where one can find amusement aboard boats and small barges whenever one pleases. But it is prohibited to all but the royal family. Leaving the gardens we went around the palace to see the magnificent courtyard; then the very city and the streets, which have recently been marked with names in the corners, just like in Paris. Subsequently we headed for an inn, where Mr Degen had ordered us food. We ate in the gardens; the whole meal cost us 30 sols each. We then had coffee on the opposite side [!] and continued to walk and look at all the splendour.

Since I had not yet seen the marble Venus in the gardens, she was shown to me. Her backside is all nude with a piece of linen covering her front, everything so well executed that it truly arouses the spectator. Mr Suther wanted to return home this evening in the same fashion we arrived, which we now started to discuss. I hesitated because of the expense, and we had some disagreement. All of those who had missed King Stanislaus wanted to stay. Mr Forsstén and Mr Ternell had also arrived too late and were eager to stay the night together with Lindh and Freitack. Mr Degen was the only one who wanted to leave with me. At that point it was decided that we should walkabout the courtyard for a while to see if King Stanislaus would show himself in one of his windows. If this happened and those who were displeased got to see what they wanted, they promised to make us company. Meanwhile we had seen Dauphin entering his coach to go to Trianon, a pleasure palace close by. We also saw the Duc de Bourgogne or the Dauphin’s eldest son, who was a small infant carried by his maidens of honour in the coach.

After having strolled about for a while, we were told that King Stanislaus was heading for a ride. The guard was immediately lined up in the courtyard; it consisted of five companies of both kinds, namely five of the Swiss Guard and five of the other. The former has red coats with blue underclothing, and the latter vice versa.

The King’s coach was presented with a team of noble dapple-grey horses; a French court servant offered us the chance to stand in one of the anti-chambers and wait for King Stanislaus, who soon came out and was seen by us all.

Afterwards we stayed for a while to watch the guard, which stood attention, being relieved. Lieutenant Freitack was confounded by the number of regiments that made their way. To him it was more a show-off than proper order. Mr Suther, Forssten and Ternell decided to stay a while longer whereas we commenced our journey home by foot. […]

| My expenses today: | |||||||||||||

| For a pot de chambre | 2.6 | ||||||||||||

| Food and coffee | 1.4 | ||||||||||||

| The wig maker | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Drinks in Saint Cloud | 4 | ||||||||||||

| Sum: | 3.22 |

*****

6th June [1755].

Although today I would have liked to have slept longer, having an agreement with Hammarberg I went up at six o’clock, got dressed and showed up at his quarters. I had expected that we would take a carriage together, but he had already mounted a horse, as always unconcerned about breaking an agreement. He pretended it had been impossible to reach me, but I told him I needn’t have been deceived if only he had let me know that he was going to call for a horse. So I walked, in spite of a slight rain, to Pont Neuf avoiding most of the rain partly in a coffeehouse, partly under the umbrella of a Savoyard. Having arrived at the bureau it proved impossible to get a voiture to Marly, though there was one to Versailles. The musketeers had already bespoken the available coaches, and there were several gentlemen waiting. A carosse de remise outside already had two people in the process of bargaining. The man before me in the bureau learned of this and invited me, which made four. It cost us 6 livres each. The company was decent, and the trip went gay and fast. We passed by the machine at Marly while talking about the renowned scholars in Sweden. [Johan Gottschalk] Wallerius was mentioned, but they knew all too little about [Carl] Linnæus. At eleven o’clock we reached Marly, where I parted from my company. Following Reisen’s instruction I climbed the street to find the coffeehouse and ask for a Swiss, but I couldn’t find him. I went to a wigmaker to mend my wig, which cost me 4 sols. I climbed the street once more to find an auberge, where I had an omelette and a demi-septier of wine, of which there was a double measure. I therefore had to pay 14 sols.

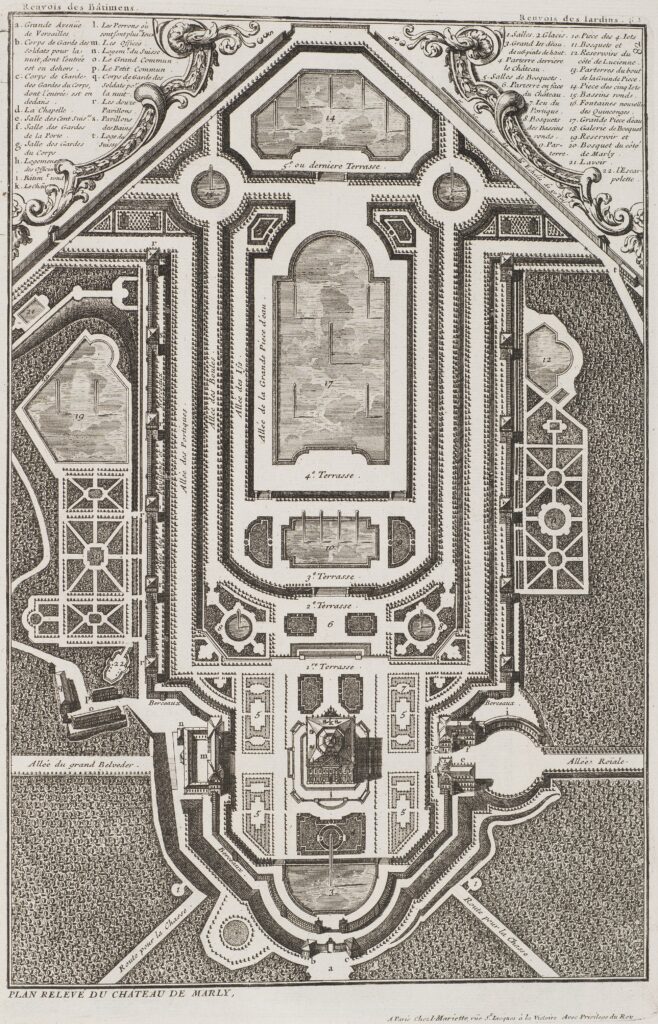

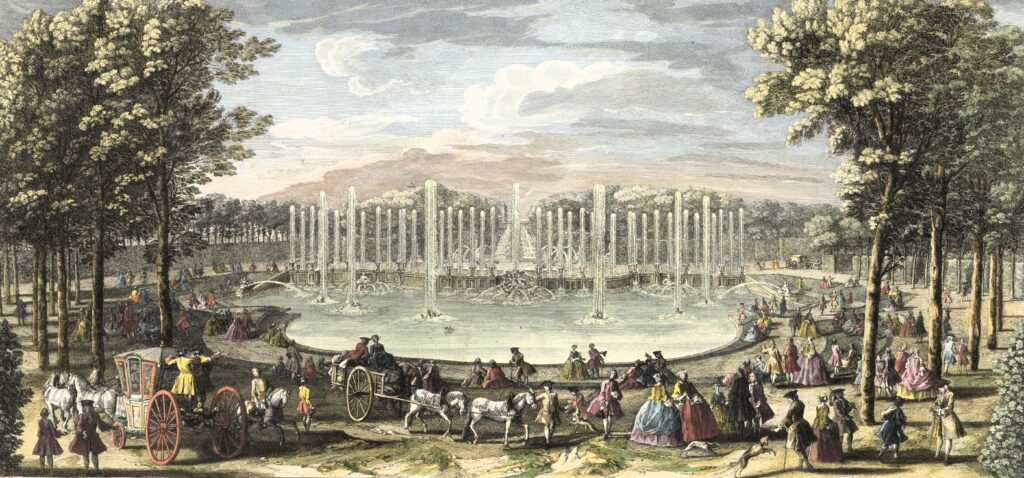

Afterwards I asked to enter the garden, went in and was astonished by its beauty and perfection. Nature has adorned the garden with thick and fully grown trees, to which art has added a pleasing order and arrangement. Surrounding it all are those great and shady trees forming the most agreeable avenues from which there are several entrances to varying rooms, seclusions and areas with marble tables and benches. At the end and beginning and corner of each avenue there are gorgeous statues, made from mythological descriptions. In the middle of the garden there are small trees and lovely parterres, adorned with statues and flower beds. At the very centre was a basin. In the basin there is a jet d’eau. A sloping alley ran from here on each side of the palace to the cascade at the top, next to one of the parterres. The palace is situated right in front of the basin, and on two sides there are six pavilions in a row. The palace is built like a square with only painted columns, about two storeys high, so small that only the royal family have their rooms there. The seigneurs reside in the pavilions. I saw all the rooms through the windows, but I did not have the chance to go inside. I walked about in the great avenues away from the burning sun. Quite by chance I met a gentleman with a large retinue at the end of one of the avenues, and he showed me all the remarkable things. He brought me right in front of the trou d’enfer, where the grand review of the troops is held. From here the whole area could be inspected. There was a bridge from the gardens that could be swung from each side over an iron pillar when the commander so desired, so that the moat prevented people from reaching the drill-ground. I tried a few times in vain to get over. On this side there were erected benches that people rented in order to see the inspection, but I did not want to make that expense. There were also tents where drinks and food were sold. For one bottle of drink, I had to pay 12 sols; there were no half-bottles. Together with cheese, this cost me 22 sols. I then wandered about in idleness, sometimes lying down on the lawns. The heat from the sun was exhausting.

The King arrived at four o’clock with his suite. Trumpets and timpani announced his coming, but I was not allowed to pass the bridge. I was told that there was another way. I was already heading home, but incidentally I found myself on this other entrance way. I therefore went to the parade ground and got a good view of the troops. They are mounted and constitute the King’s guard of the cavalry. Together they are called Maison du Roi and consist of: 1st the garde du corps, which is the most numerous, viz. 1,400 men; 2nd the musketeers, which are of two kinds: mousquetaires noirs, wearing silver laces and blue cloaks, and mousquetaires gris, wearing gold laces and white and red cloaks; 3rd gens d’armes in red uniforms with gold laces; 4th chevaux legers, in like clothing but separated from the former by a small silver-lace rib within gold lace around the buttonholes. The Duke of Savoy is their captain. 5th The least numerous are the grenadiers à cheval, like the garde du corps dressed in blue uniforms with gold laces but wearing a leather bonnet like our coachmen and provosts and with sabres instead of rapiers.

When I had passed by all of these and pushed my way between coaches and horses I paused and happened to catch a quick glance of the King. But I advanced further and came to be standing right in front of the centre just as everyone was about to march past the King. I asked a coachman to let me climb his seat to get a good view, which he allowed me. Other people of quality did the same. He showed the place where the King was, but it took me quite a while before I could spot him. Apart from the King I was also pointed to the Dauphin and, next to the King, the Comte de Brioche, who is a grandseigneur de France, the Duc d’Orleans, the Duc de Condé and yet another.

All the companies passed by. The captain lowered his sword for the King and the standards saluted. The King was the first to take his hat off, followed by all the others, for each captain that passed.

Thus, I came to see the renowned Maison du Roi, which is said to be 2,500 man strong.

| Because gardes du corps makes | 1,400 | ||||||||||

| mousquetaires noirs | 200 | ||||||||||

| mousquetaires gris | 200 | ||||||||||

| gens d’armes | 200 | ||||||||||

| chevaux legers | 200 | ||||||||||

| and grenadiers à cheval | 130 |

Moreover, there are surnumeraires of an uncertain quantity, which, praeterpropter, could add up to the whole sum.

The King’s foot guard is more numerous but these [the horse guard] are more shining. Garde française consists of 33 companies and each company has [lacuna]. Garde de suisse consists of [lacuna].

This so-called Maison du Roi is illustrious from the battle of Fontenoy, where they, under the command of Comte de Saxe, decided the outcome of a combat which otherwise seemed disastrous to the French. Since the troops’ maintenance is a costly affair and each soldier cannot be paid in accordance with his merit, it is customary to choose youths of quality and wealth, who are able to subsist on their own interest. After serving a number of years in the Maison du Roi they are certain of a company in the army.

After having seen everything, I took off for home, passing several gardens. In the village I took orchade [a non-alcoholic beverage] for 9 sols and continued immediately. I tried to find a shorter way than the public highway, on which I arrived. Before long I was lost and would have ended up at Saint Germain if not a person I asked had directed me to take to the right.

I went tout de suite to the machine, halted there and refreshed myself with eggs and wine, which cost 8 sols. I then went above the machine to have a look at it. There were 14 wheels in the Seine stream. They were turned by the water and moved all the iron bars that were mounted one after the other all the way up the hill. These in turn move about two kinds of pumps, first those which they call pomps aspirans, which pull the water up, and then pomps fondants, which subsequently push it forward. The water is first moved 150 feet up. There it is gathered in a reservoir from which there is an additional pump system for the next conduit of 150 feet leading to another reservoir. Finally, the water is led 200 feet, ending up in the main reservoir. From there great channels lead to all localities that are supplied with this water, including Versailles and Marly. It is said that this machine could have been simpler and that repairs are quite expensive.

After having examined the machine, I took to the road. I met some priests who recommended me to take a chariot in order not to exhaust myself, an advice I heeded with respect to my arm. There was room in the second chariot I met, and although it jolted and I came to sit in the rear, it was nonetheless better than walking. It cost 20 sols, which were to be paid in advance. My wigmaker’s garçon became my company since he was already in the chariot and made place for me. We were 16 people.

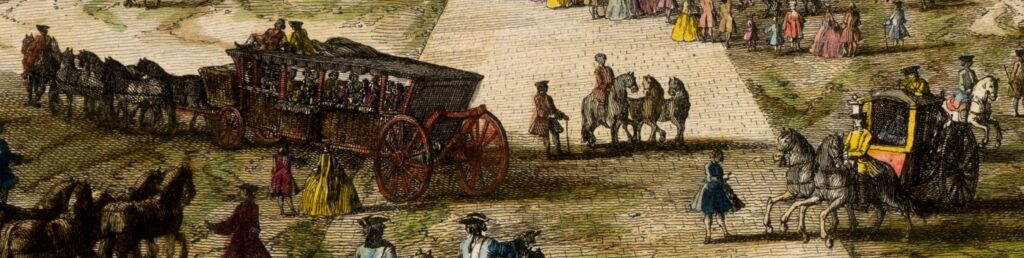

On the road there were an étonnant nombre of coaches, cabriolets and riding horses passing us by, not neglecting the French manner of sneering at our lowly voiture.

At the bridge at Neuilly, where only one coach at the time could pass and had to hold to pay, we waited for more than two hours before it was our turn to pass. From there we went downhill at such a slow pace that we did not reach faubourg Saint Honoré until one o’clock. We got off at the boulevard. I had the company of the wigmaker’s garçon and arrived home at half past one. Suther was not home yet; he would leave tomorrow, but [illegible] Söderberg was there. I went to bed immediately, quite tired.

| My expenses today: | |||||||||||||

| Orchade in town | 6 | ||||||||||||

| The coach to Marly | 3.24 | ||||||||||||

| Refreshments at the first place | 14 | ||||||||||||

| and at the second 22 sols | 1.4 | ||||||||||||

| dito orchade at departure | 9 | ||||||||||||

| payment for the coach | 20 | ||||||||||||

| [Total:] | 5.31 |

*****

24th August [1755]. Sunday

While I was still in bed Messieurs Pfeiffers and then Mester and a German surgeon by the name of Schmitt arrived to commence our trip to Versailles. I was waiting for a pair of socks but soon got up, got dressed quickly and was ready at half past seven. We went directly to Pont Royal where we embarked a batelet [small boat] to take us to Saint Cloud. From here there is also a galiote [galley boat]. Batelets are paid 5 sols. There were women with us. It was a bit rainy and windy. We arrived at Saint Cloud précisément below the so-called Bourbonderie, where the King holds his cuisine together with some gentlemen when he is in Bellou. Our journey continued after we had had breakfast of lamb steak and wine. We were shown the route to Marly past the garden of Saint Cloud and all the way through the park. A German soldier showed us the way and so we walked past long stretches of vineyards where we stuffed ourselves with grapes. We thought we were lost a couple of times, but asking our way we finally reached the main road leading to the machine at Marly. Here we went in, had something to eat and engaged a person who showed us the machine. I took a close look at the taps, comprising the cogwheels that move the wheels, and how they pull the pumps and raise and force the water. We then followed the channels uphill, inspected the first reservoirs and so on, continued through the machine until we reached the second château, where we met a Swiss at a gate who assumed to show us the arcades. Here I changed my louis d’or. He took his key, led us through a gate to a courtyard where all the channels converge to a house where a new machine is drawn vertically upside a wall, leading to a reservoir from which horizontal channels lead down to Marly. Up here the canals are supported by high pillars rising to the sky with vaulted intervals between them, which make a splendid impression of great vaults (arcades). To get there we had to climb a flight of stairs as if to a tower. We were shown all the five canals leading into the reservoir, which was marked in inches at the brim to show how much water was coming in. We were told that for two canals or tuyaux there are eighteen pumps, and for three [there are] twelve; consequently, two are a third bigger than the three etc.

We descended. I paid 35 sols. We were shown the way to Marly. This way through the machine is shorter than the other.

We soon reached the gardens of Marly and saw the place where all the canals converge at the gate where we entered. The waters were running but our first concern was to see the palace, which the Swiss was reluctant to allow, showing us instead to the waters. I told him that we were foreigners and had come expressly for the palace, and after a while of waiting we were let in, but I had a hard time convincing all my companions. Gratuities were given to a Swiss. From there we went to see the garden, first the cascade up along a lengthy [illegible] where Mr Carl Fredric Pfeiffer to his brother’s great amusement became involved in a small démêlé with me and was so disturbed that he decided to visit the gardens alone. We inspected all the eaux d’artifice until they were shut down. I tried to encourage Pfeiffer once more, but he showered me with stupid remarks and showed no gentleness. We were now about to move on, but a Swiss at the gate asked us if we wanted something to eat. We had a delicious joint of veal which, together with salad, dessert and wine, cost no more than 6 livres 10 sols altogether. We ate in a house beside the palace. If there had been a bed there, we would all have taken a rest, but to our luck we were obligated to go to Versailles this evening. When leaving we paid 2 sols to a person who showed us the way. The walk was pleasant in the moonlight and on the smooth pavement, and we continued our route under gaiety until we arrived at nine o’clock. We were told that there was going to be grand couvert this evening and we therefore went to a wigmaker to have our hairs set and tidied up for 3 livres altogether. Here we were assigned to a neat lodging. We went to the palace despite the late hour and although we had been told that there would be no couvert. My companions were only shown the path and the grand gallery to find their way around tomorrow.

We soon went down. The others were satisfied to have their hair at least partly in order for tomorrow. For 6 livres we got to rest all five of us, and the room had three beds. I slept together with Mr Mester the first night, and Mr Schmitt with Carl Fredric Pfeiffer. We did not sleep bad, woke at eight o’clock.

25th August [1755].

Everyone anxious to soon get dressed, we sent for our wigmaker who sent two garçons. During the mending I informed myself on what tour we ought to take in order to see everything worth seeing today. It is now Fête du Roi, when the waters flow and all the apartments are open to the people. We were duly informed, and after having got dressed our route were as follows. Since it was now ten o’clock, we ought to hurry to the menagerie, where all the live animals in the King’s possession can be seen. We went there through the gardens all the way down but then through the fences on the left-hand side. After we arrived, we had to wait for a while with the crowd until we first got to see the palace [of the menagerie]; in a salon there were pictures of all the animals which were later to be presented. The apartments were mostly decorated with mirrors and gilt inside.

When these had been inspected, we went down. We were led through the gates to the cours, where there were certain departments for the animals, like small pavilions. What I had not seen before were mostly a large amount of small and big birds, among them an ostrich. One yard was exclusively for lions, tigers, and guenons. I also saw camels and dromedaries for the first time. A wolf was also installed here. Strange kinds of bucks and oxen and much else. We had planned to go from here to Trianon, but it was now too late, and we decided to the see the royal family leave Mass and hastened back. When we arrived, they were already in church. We stayed in the room with the clock with an intricate machine, representing King Louis XIV’s equestrian statue which, when the clock strikes, rides through a temple gate while the sky simultaneously opens and an angel from Heaven crowns the King. On both sides of the King stands his guard in cuirass, and a little beforehand two cocks start clapping their wings, thus giving sign of the passing of time.

After having inspected this, we took position to get a good view of the royals, who arrived soon after the strike of twelve. Dauphin went first followed by Le Roi, then Mesdames[,] Madame Le Dauphine and lastly La Reine. They all went to the King’s room to greet him on his day. We positioned ourselves outside and saw them pass by on their way to their rooms, when we also got to see les enfants de France. I had never seen Madame before.

Following advice, we were then planning to go inside Clagny but lingered for a while at the palace in order to see les États Ecclésiastiques and all the Seigneurs on their way to salute the King. I now got to know Prince de Dombes, Comte Charleroi and Prince de Conti, and later, outside the rooms of Mesdames, Madame Pompadour.

We pursued our plan to visit Clagny to the extent that we could, but we only got as far as the gate. We were told that today there was going to be a big repast called repas de Languedoc for all Seigneurs. Prince de Dombes is hosting the repast, but this gentleman never lets anyone see his palace, which is held to be quite splendid.

We thus went back, having a long search for an affordable bit of food; finally, we had to enter a place where it cost us 40 sols each. But we had a decent meal.

In the afternoon we were anxious to see all the waters running, which we also managed to. Some ladies who were being transported in carillons by Swiss were, on both sides, attended by a large company which we followed, although our own group was dispersed. I mostly saw the waters on the left side. The cascades at the bassins were not fully opened before la compagnie arrived.

Around the one where everything always ends the crowd formed a large amphitheatre, which made a very nice impression. It is called bassin de Neptune. Here I came upon Mr Mester and a Dane. We went into the palace, where I got to see the King’s bedchamber. Then we went to have orgeat and when we returned, we ran into the Pfeiffers, who said they had been looking for us. I asked for the room where the grand couvert is held, but when we got to the doorway there were no means to get past the musketeers standing guard. Yet, I soon helped myself through the first door into the room where the whole service was standing and where the food is kept warm. But here was also the officer of the guard who would not take the trouble of letting anyone in. Strangers, he told me, could even less hope to be let in since they had not been introduced. After having spoken to him as polite and gentle as I could I was ultimately let in. I got a good look of the whole royal family and was standing on the right side beneath the end of the table where Mr Le Dauphin is sitting. I especially got to know all Mesdames, with whom the King himself mostly spoke. When everything was over all the other entered after the guard had opened the entranceway and the royalties had gone to their rooms. They all stayed with me, and we waited attentively until Mesdames left, which a rather polite courtier permitted us. We followed them at a distance and then went home to our quarters from the night before.

26th August [1755].

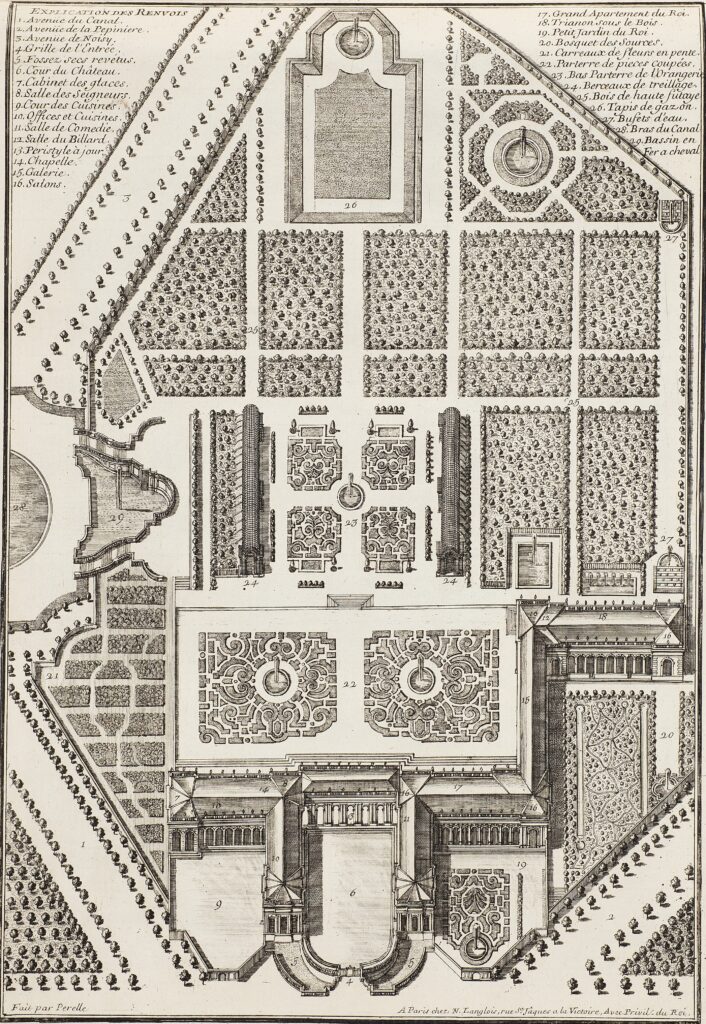

Awoken only at nine o’clock we decided to see Trianon; we did not mend our hair but hurried along after having had breakfast at the coffeehouse. The path went through the garden opposite the menagerie, past a barrier of earth and through a pretty avenue. Upon arrival, we addressed the Swiss who without hesitation showed us the whole palace. It is rare that any other royalty than Le Roi himself comes to visit, and there are no chambers for the others. The apartments are covered with paintings of the greatest masters, mostly depicting the battles of Louis XIV. The gallery was the most beautiful room, which we saved to the end. Paid 3 livres. We then walked about the garden, which was said to be almost as big as that of Versailles, but not having as many eaux d’artifices. It was nearing twelve o’clock, so we hurried to see the royalties going to and from Mass. We made it just as they entered. We were let into the church where we had a good look at everyone and heard some fine music. This morning Le Roi had left early to hunt and had already visited Mass. When they [the royal family] had left I parted from Mr Pfeiffer since he wanted to see the clockwork, which I had seen enough of yesterday. I wanted to hurry into the Queen’s room before she herself entered, which I also managed and got a good look at the corner salon which they call Salon de [Paix]. At the same moment Mr Le Dauphin arrived and I had to leave trough the other door. I bumped into Mester and Schmitt and went to the other side in order to see the bedroom, but since the bed was not yet made, we were told to wait. Meanwhile we tried in vain to find Mr Pfeiffer. Next, we went to the stables, écurie du Roi and celle des dames. In la petite écurie we saw the small horses that Duc de Bourgogne had been given by the Sultan as well as all sorts of the King’s horses. Young grooms showed us around and did not forget to demand gratuities. We looked once more for Mr Pfeiffer, but when he was not to be found I stayed in the room where Mr Le Dauphin and Madame La Dauphine dined and got a fair idea of their table. When I got out Mr Mester had still not found Pfeiffer. We ran across Baron Bunge and discussed going to Bellevue, but we were told that the King might be there today. Once more we tried in vain to find our lost friends in the garden. I left with the intention of seeing Mesdames dine, but I was not admitted. Instead, I walked for a while in the gallery and incidentally saw the Pfeiffers, whom I went to meet. Mr Carl Fredric was grumpy again. We all went to the coffeehouse and then headed off home. Mr Pfeiffer hardly spoke during the whole trip. We took the Paris pavée until we reached the gate to a park; we went inside in order to go directly to Meudon, which is Dauphin’s palace. By the thoroughfare in the park is a small building in disrepair called la Calotte where the King rests on his hunts. Now it is all abandoned. We had a good look around and were most enthralled by its beautiful prospect.

On arrival at Meudon we found two palaces, an old and a new one. We first looked for the Swiss at the old one, which Dauphin himself always occupies when he is here. We inspected the rooms which are all in a goût with panelling and gilt mouldings following old customs, yet more modern than Fontainebleau and Madrid. Salon des Muses and the beautiful gallery are mostly to be considered. The prospect from this palace is admirable as it is situated very high.

From the old palace we went to see the new, but the Swiss was not at home; however, we had some refreshments with wine, butter and bread, which cost us no more than 40 sols.

We then set out for home; the rain was over us, but we made haste so that we were home at nine o’clock. Mr Mester and I decided to dine at Palais [Royal], but Messieurs Pfeiffer went home. When we stopped by Mr Martinau’s door he was already in bed, but he was so brightened by our homecoming that he speedily got up, got dressed and accompanied us. We visited Mr Pfeiffer with the intention to bring him along, but he was all too tired. We thus went only the three of us, dined well and then went to rest.

My expenses for the trip amounts to 12 livres in all or 7 daler, 16 öre.